The Japanese sword, renowned for its elegance and craftsmanship, is a testament to the artistry and skill of its makers. These swords, typically curved and single-edged, reached their zenith during the Heian Period (794-1185) and were integral to the samurai, Japan’s warrior class, until the late 19th century. Originating from Chinese steel technology introduced by the fifth century AD, the Japanese sword, or nihonto, is not only a weapon but also a revered art form with deep spiritual significance. It is one of the three sacred treasures of the Japanese imperial regalia and is often linked to Buddhist symbolism.

In the traditional Japanese swordsmith’s workshop, a shrine dedicated to the craft’s deity is a common sight. The sword-making process is steeped in rituals of purification, reflecting the Shinto belief in the harmony between nature deities and human endeavors. The variations in length, shape, and metallurgical properties of Japanese swords over the centuries allow experts to determine their age and origin with precision.

Blade Construction

The creation of a Japanese sword involves the fusion of steels with varying qualities to produce a blade with a hard exterior and a softer core. The steel is purified, and its carbon content is adjusted before being folded multiple times to form a laminated structure. This block is then shaped through hammering and filing, followed by heat treatment. The grain pattern, known as jihada, emerges from the folding process, while the final shape is achieved through meticulous hammering and filing.

A crucial step in the process is the heating and quenching of the blade to harden it. The blade is coated with a mixture of clay, charcoal, and steel dust, which is scraped off along the cutting edge. After being heated to a red-hot state, the blade is quenched in cold water. The varying thickness of the clay affects the cooling rate, influencing the crystalline structures formed in the steel. This results in the hamon, a distinctive whitish line along the edge, and the jihada on the blade’s flat surface. The hamon is the hardest part of the blade, allowing it to be razor-sharp.

The sword’s mechanical properties and aesthetic appeal depend on the skillful execution of the quenching process. Polishing is equally crucial, involving over twenty grades of stone to reveal the blade’s textures and protect it against corrosion. The polisher, or togishi, ensures the blade’s lines are smooth and angles well-defined, enhancing its beauty and durability.

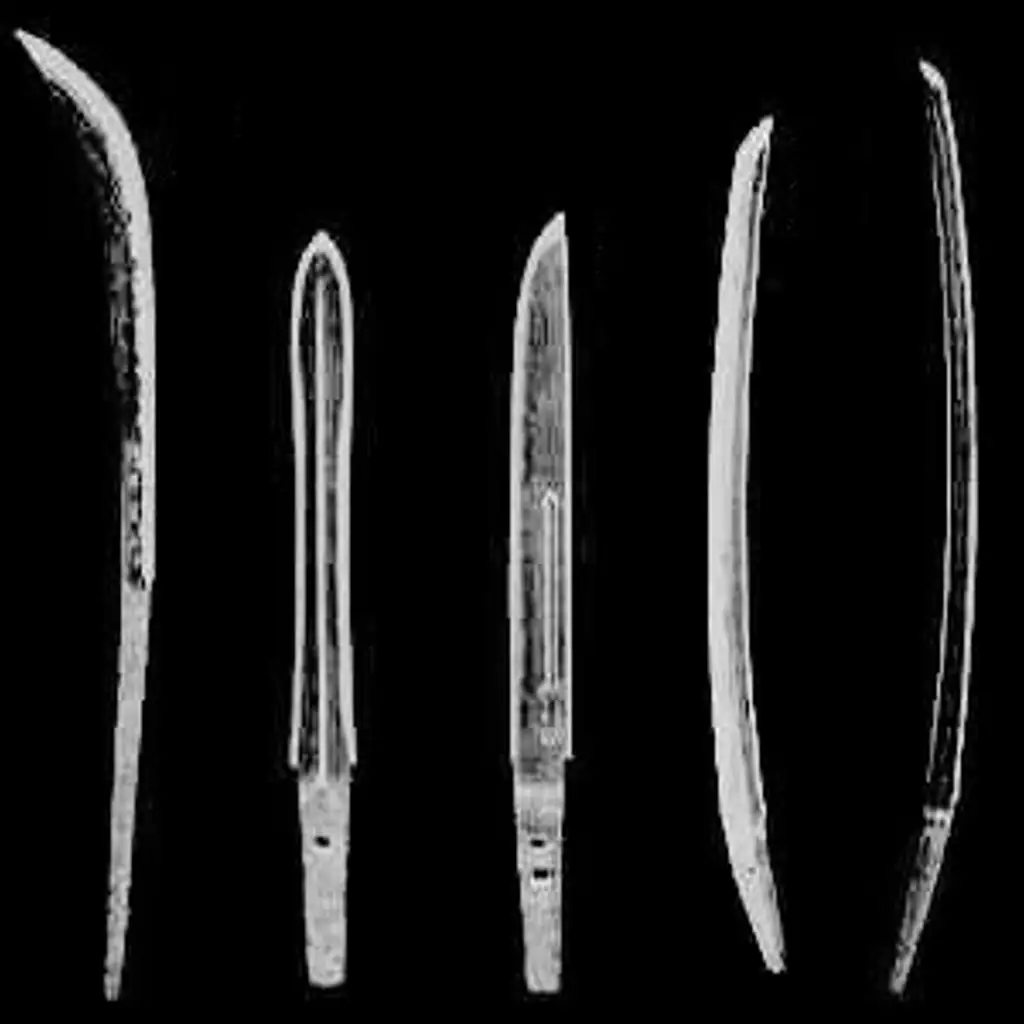

Varieties of Japanese Swords

Japanese swords are traditionally categorized by length, although terminology has evolved over time. The term “katana” is often used to refer to any Japanese sword.

- Tachi: Long swords over 60 cm, often reaching 80 cm, used by armored samurai on horseback from the Heian period.

- Katana: Used from the Muromachi period, these swords are worn through the sash, edge facing up, and are over 60 cm long. Only samurai were permitted to wear a katana.

- Wakizashi: A shorter sword between 30 cm and 60 cm, worn at all times by samurai, often paired with a katana.

- Tantō: A blade between 15 cm and 30 cm, designed primarily for stabbing but also capable of slashing.

- Yari: A spear with a blade for cutting and thrusting, typically double-edged, sometimes with additional blades.

- Naginata: A pole-arm with a curved, single-edged blade that broadens towards the point.

Classification by Style and Era

Japanese swords can also be classified by style and age:

- Jokoto: Also known as chokuto, these are straight swords made before the tenth century, influenced by Chinese designs.

- Koto: Meaning “old sword,” this term refers to swords made from the Heian period through the Keicho Era (1596-1615), classified into five traditions: Yamashiro, Yamato, Bizen, Soshu, and Mino.

- Shinto: “New swords” made from the Keicho Era to the An’ei Era (1772-1781), reflecting a mix of local traditions and a new forging style.

- Shinshinto: “New new swords” made after 1781 until 1876, when the Meiji government banned sword-wearing. These swords emphasized individual styles over traditional schools.

Following the Edo period, Japanese sword production transitioned from weaponry to art, leading to classifications such as Gendaito (modern sword) and Shinshakuto (newly made sword).